When it comes to female heroes of the Civil War, there are many familiar names. Clara Barton took fire tending wounds on battlefields. Harriet Tubman helped hundreds of slaves escape to freedom. And Sarah Rosetta Wakeman (posing as a man named Lyons Wakeman) fought as a Union soldier with the 153rd New York Volunteer Infantry, Company H.

But there were heroines whose achievements might be a little sly—the female spies of the Civil War. Perhaps the most famous among them was Belle Boyd. Belle was known for charming Union soldiers, extracting intelligence, and passing it on to the Confederates. Ultimately she was captured, but fell in love with – and married - her jailor (a familiar theme).

Belle was not alone. Hundreds of women served as spies for the Union and Confederacy during the Civil War. They often carried information about the enemy's plans, troop size, and fortifications on scraps of paper or fabric which they sewed into their blouses and petticoats or rolled into their hair. Spying redefined their traditional roles as housewives, mothers, and eligible bachelorettes and made them an important part of the war effort.

In fact, Confederate military leaders were known to actively recruit women for undercover operations, mainly because of their familiarity with local customs and geography. Elaborate spy networks were established with women serving at all levels.

Fairfax County was home to two of these female spies and their tales are as rich as the covert information they handed over to General JEB Stuart and Colonel John S. Mosby. Here are their stories.

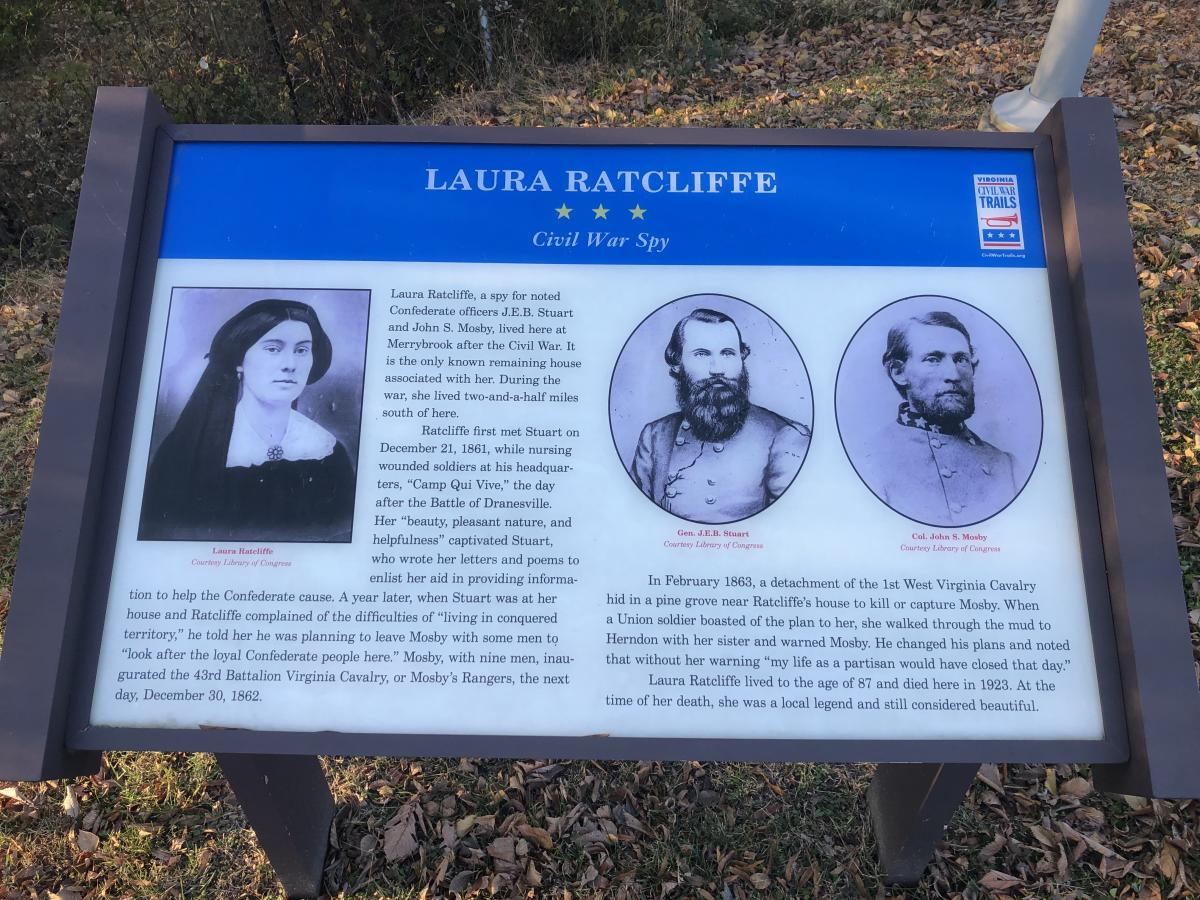

Laura Ratcliffe caught the eye of both JEB Stuart and John Mosby.

Laura Ratcliffe was born in 1836 in Fairfax County. Her home in Herndon was sometimes used as a headquarters by Confederate raider, John Mosby.

In one instance, a Union Lieutenant came to the Ratcliffe home to buy milk. He knew of her fondness for Mosby and said, “I know you would give Mosby any information in your possession, but as you have no horses and the mud is too deep for women folks to walk, you can’t tell him. So the next you hear of your ‘pet,’ he will be either dead or our prisoner.”

Laura called his bluff and trudged through the sucking mud to warn Mosby. As a result, he evaded capture and lived to be a prominent thorn in the Union’s side throughout the war.

She was also a prolific spy for JEB Stuart. Stuart showed his appreciation by giving her an album and a gold watch chain. The album contained four poems, two of which were specifically written for Ratcliffe by Stuart. The poems were considered “love” poems and the album was inscribed, “Presented to Miss Laura Ratcliffe by her soldier-friend as a token of his high appreciation of her patriotism, admiration of her virtues, and pledge of his lasting esteem.” But there was no evidence of a real love story between them—just flirtation, charm, and spycraft.

Later in life, Laura seldom mentioned her role as a spy and shunned publicity about her role as a provider for the Confederacy. She married well to a neighbor who was sympathetic to the north. She died at the age of 87. Her grave is hidden within a hedge in front of the Washington Dulles Marriott Suites hotel.

Antonia Ford spied for the Confederacy, then married her Union captor.

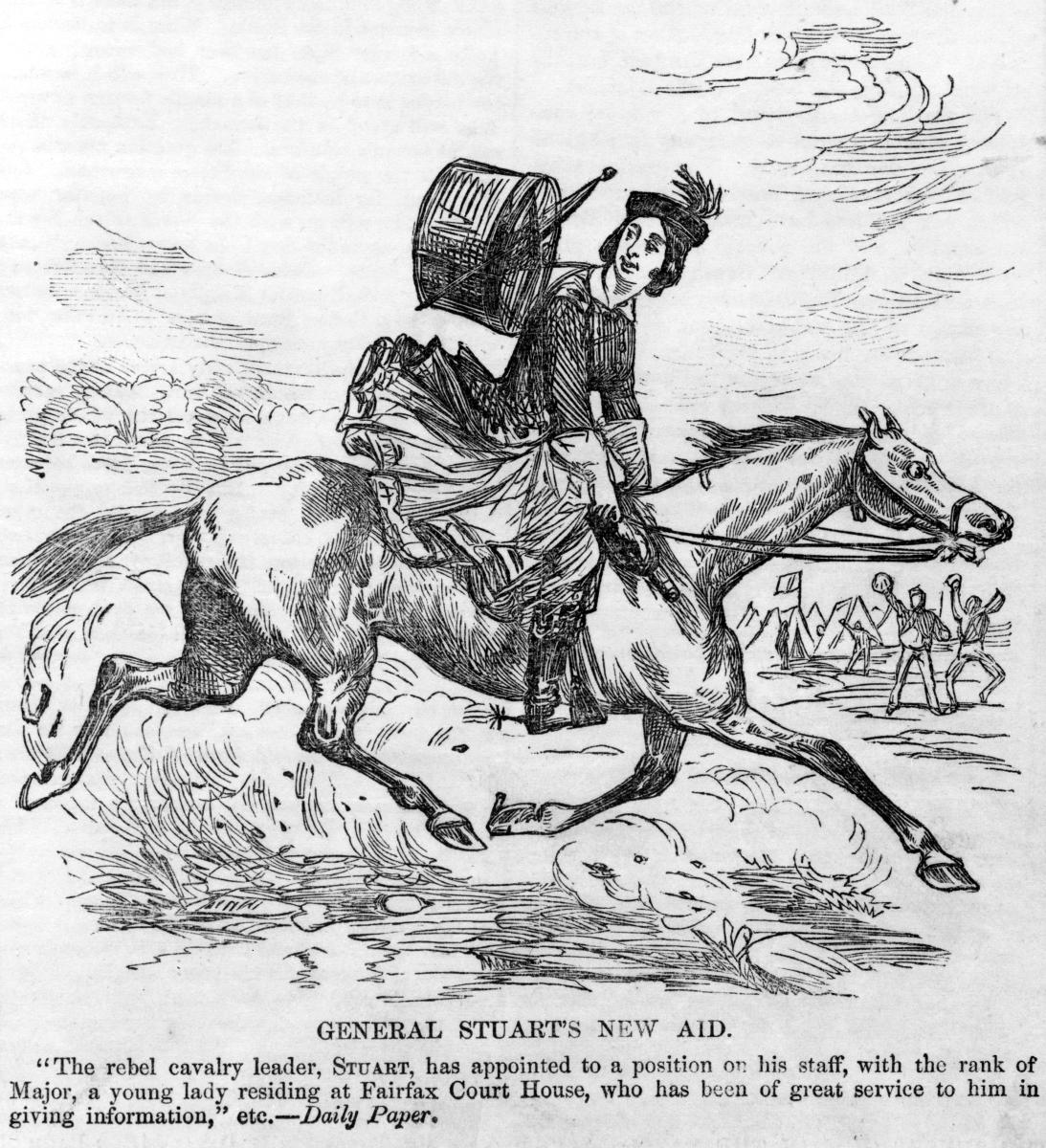

On March 15, 1863, Union soldiers roused Antonia Ford from her bed across from the Fairfax Courthouse. The soldiers demanded she take a loyalty oath to the Union. She refused. On suspicion of espionage, her home was searched, and Union officers found $6,000 in Confederate currency and a signed letter from Major General J.E.B. Stuart giving her an honorary “lieutenant and aid-de-camp” title. She was immediately arrested.

Just twenty-three years old at the onset of the war, Antonia entertained soldiers at her home and shared the information she overheard with JEB Stuart and John S. Mosby. After the Confederate victory at the First Battle of Manassas/Bull Run, Stuart sent her the signed letter that eventually incriminated her in her arrest.

The arrest was based on her involvement in the capture of 58 horses and 33 Union prisoners by Col. John S. Mosby. On March 8, 1863, Mosby snuck into Union-occupied Fairfax Court House with 29 of his raiders. He snuck into Union General Edwin H. Stoughton’s tent and woke him. When woken, this exchange ensued:

“Do you know who I am?” Stoughton exclaimed.

“Do you know Mosby, general?” Mosby answered.

“Yes! Have you got the rascal?”

“No, but he has got you!”

Antonia was arrested a week later. When President Abraham Lincoln heard of this capture, he reportedly said he did not mind the loss of the general, since he could just confer another one, but “those horses cost $125 apiece!”

A counter-intelligence spy was soon dispatched to the Ford home. Frances Jamieson, a female Union spy, stayed at the Ford home for several days, befriended the family, and eventually won Antonia Ford’s trust. Over the course of their time together, Ford told Jamieson about her espionage activities and showed her the signed “honorary lieutenant and aid-de-camp” letter. This evidence was enough to secure her arrest.

Ford was sent to the Old Capital Prison in Washington, D.C. Her escorting captor was Major Joseph Clapp Willard. At 41, Willard was older for a Union soldier and he was married. He was an avid businessman and helped run the prosperous Willard Hotel with his brother Henry. Then the unexpected happened. The Confederate spy fell in love with her Union jailor. She ultimately took the oath to the Union.

After Antonia was freed, the romance continued. She wrote:

"Major, you know I love you, but . . . [my] parents and relatives would be mortified to death; acquaintances would disown me; it would be illegal, and above all it would be wrong . . . I would make you 'the luckiest man in the world' if I could without compromising myself . . . You ask for my 'heart and hand.' The heart is yours already. When your hand is free and you can claim mine before the world, then that also is yours."

Willard divorced his wife and resigned from the Union Army. The two married and were together until death. When asked why she married Willard in the first place, Ford jokingly told a friend: "I knew I could not revenge myself on the nation but was fully capable of tormenting one Yankee to death, so I took the Major."

Antonia Ford Willard is buried at Oak Hill Cemetery.

Victorian novelists could not have come up with better espionage stories—a young spy that elicited love poems from a Confederate General and another who got arrested and married her Union captor. These Virginia belles are just two of the fascinating stories you’ll find on a Civil War tour of Fairfax County. Visit and discover these remarkable women, a few suffragists and Clara Barton herself during Women’s History Month in Fairfax County.