A large part of Fairfax County's creative spirit flourishes at the Workhouse Arts Center, known for its galleries and exhibitions, performing arts experiences, and all things imaginative. However, beneath the surface of its extensive art collection is a revolutionary story of resilience that changed the face of American politics as we know it.

Prior to becoming a vibrant center for the arts, the structure you see today was once part of the Lorton/DC Correctional Complex. In January of 1917, the National Woman's Party began picketing the White House to demand the right to vote. Not only were they met with imprisonment, but also unimaginable brutality and dehumanization. The determination and struggle of these suffragists would be one of the major turning points in the ratification of the 19th Amendment, securing a woman's right to vote in America.

This month, we revisit our series on Women's History in #FXVA by taking a deep dive into this extraordinary story.

The Lorton/DC Correctional Complex

Photo Courtesy of the Workhouse Arts Center

Constructed in 1910 by the first prisoners of the complex, the Lorton Correctional Facility was championed by the Theodore Roosevelt Administration as a one-of-a-kind men's prison to focus on the reformation of inmates through hard work and trades. Inmates were given tasks such as constructing buildings and working on the farm. In 1912, the Women's Workhouse was established on a nearby site, where inmates did domestic tasks such as laundry and working in the kitchen. Sentences at both institutions were of short duration, as many of the imprisoned committed nonviolent offenses.

The Silent Sentinels

Photo Courtesy of the Workhouse Arts Center from the Library of Congress

In 1917, female protestors known as the "Silent Sentinels" began peacefully picketing the White House six days a week, calling on President Woodrow Wilson to create a federally-enforced law supporting a woman's right to vote. Adorned in dresses with white, gold, and purple sashes, they touted signs with monikers such as "Mr. President, How Long Must Women Wait for Liberty?" The initial response from the public and administration slated towards indifference, but this attitude began to shift when the United States entered World War I. While the mainstream suffrage movement rallied behind the war effort, the Sentinels continued to picket during the war - a move deemed "unpatriotic" that enraged many of the public and media. Police began to become more stringent against the picketers, arresting them for "obstructing traffic" and other minor violations. Initially, the women were released without penalty, but the intensifying conflict resulted in more severe punishments: being sentenced to upwards of 60 days in prison. Many of these women were sent to the Lorton Correctional Facility.

By that point in time, the facility's conditions were less than desirable. Suffragists were subjected to worm-infested food, filthy bedding, and poor treatment. To oppose these conditions, the imprisoned women began hunger strikes. In response, prison guards began forcibly strapping women into chairs and force-feeding them using funnels and rubber tubes placed in their nostrils. While this ongoing treatment was already egregious, it inevitably worsened on one pivotal night that sent waves of horror through the nation.

A Night of Terror

Photo Courtesy of the Workhouse Arts Center from the Library of Congress

On November 14, 1917, the culmination of months of tension between suffragists and prison security reared its ugly head. Aggravated by the resistance of the imprisoned women, the prison superintendent ordered guards to mercilessly crack down on their stalwartness. Guards dragged suffragists down dark hallways and threw them into filthy punishment cells. Suffragist Dorothy Day was slammed twice over the arm of an iron bench. Lucy Burns was forced to stand all night, arms shackled over her head whilst receiving threats of a buckle gag and a straitjacket from guards. Dora Lewis was knocked unconscious after her head was rammed into an iron bed. Having watched Lewis's harm, Alice Cosu suffered a heart attack that was left untreated until the next day. This infamous turn of events became known as "The Night of Terror."

The Release

Photo Courtesy of the Workhouse Arts Center from the Library of Congress

Photo Courtesy of the Workhouse Arts Center from the Library of Congress

In the wake of the attacks, the news of what transpired reached suffragists and allies outside of the correctional facility and quickly spread throughout the nation. Public disgust ensued, and pressure was firmly placed on elected officials to take action. The suffragists at the Workhouse were released days later as a result, appearing in front of a judge in the District Court who made a ruling for their release. Their arrests were later ruled unconstitutional. By early 1918, President Woodrow Wilson succumbed to the mounting public pressure stemming from the women's mistreatment, as well as ongoing protests by the Silent Sentinels, and announced support for Congress to act on the federal suffrage amendment. While it passed in the House, it failed in the Senate. The Silent Sentinels continued to arrange protests and take action all the way until the final ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920.

The Workhouse Today

Photo by Mina Habibi for the Workhouse Arts Center

Photo by Mina Habibi for the Workhouse Arts Center

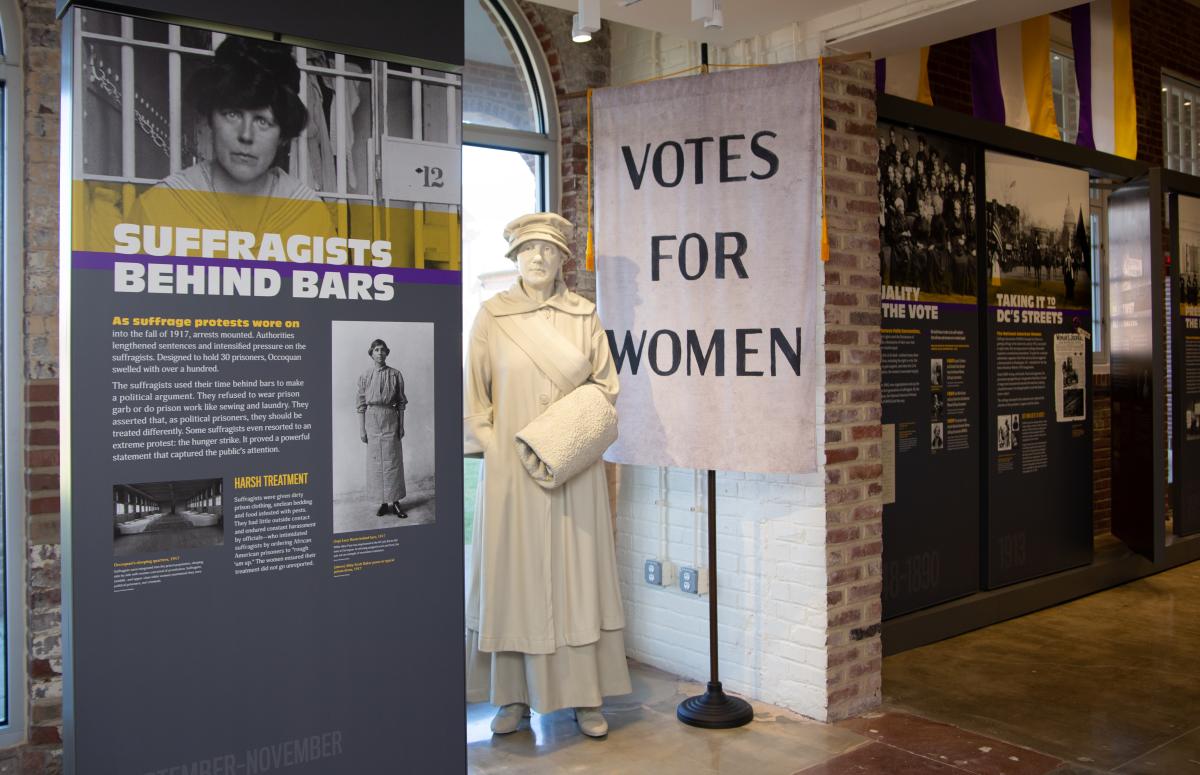

Today, despite its dark past, the repurposed Workhouse Arts Center has now become a space of striking beauty. A guard tower with stained glass windows, the bedazzled LOVEworks sign, intricate art galleries, and collective performance spaces stand on the foundation of what was formerly cell blocks. However, the Workhouse Arts Center is resolute in its commitment to ensuring this remarkable history is not forgotten.

In celebration of the recent 100th Anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, the Center opened the Lucy Burns Museum, which documents the story of the 91 years of prison history and the suffragists who were imprisoned. Visitors can see artifacts, learn more about its history, view original log documents, and even walk through a cell block remodeled after the suffragist's quarters. In building W-16, just steps away from the museum, visitors can marvel at the stunning new mural by artist Sunny Mullarkey entitled "Equality for All," commissioned by the Women's Suffrage Centennial Commission, which depicts suffrage leaders Carrie Chapman Catt, Mary Church Terrell, Alice Paul, and Ida B. Wells amid silhouettes of marching suffragists.

Courtesy Turning Point Suffragist Memorial Association

Courtesy Turning Point Suffragist Memorial Association

You can also visit nearby Occoquan Regional Park to explore the Turning Point Suffragist Memorial, a national memorial that pays tribute to ALL of the women who fought during the suffrage movement and is the first of its kind in America. Snap your photo in front of a piece of the ACTUAL White House Fence that the suffragists picketed in front of in 1917 (on loan from the National Park Service), learn their stories as you walk by 19 educational stations, reflect on their struggle in the beautiful meditation garden, and visit with several bronze statues of key suffrage leaders at this new important site in women's history.

To learn more about female trailblazers and women's history, visit our HERstory page and be sure to read our Insider Blog each week in March for a new article about women's history in #FXVA.